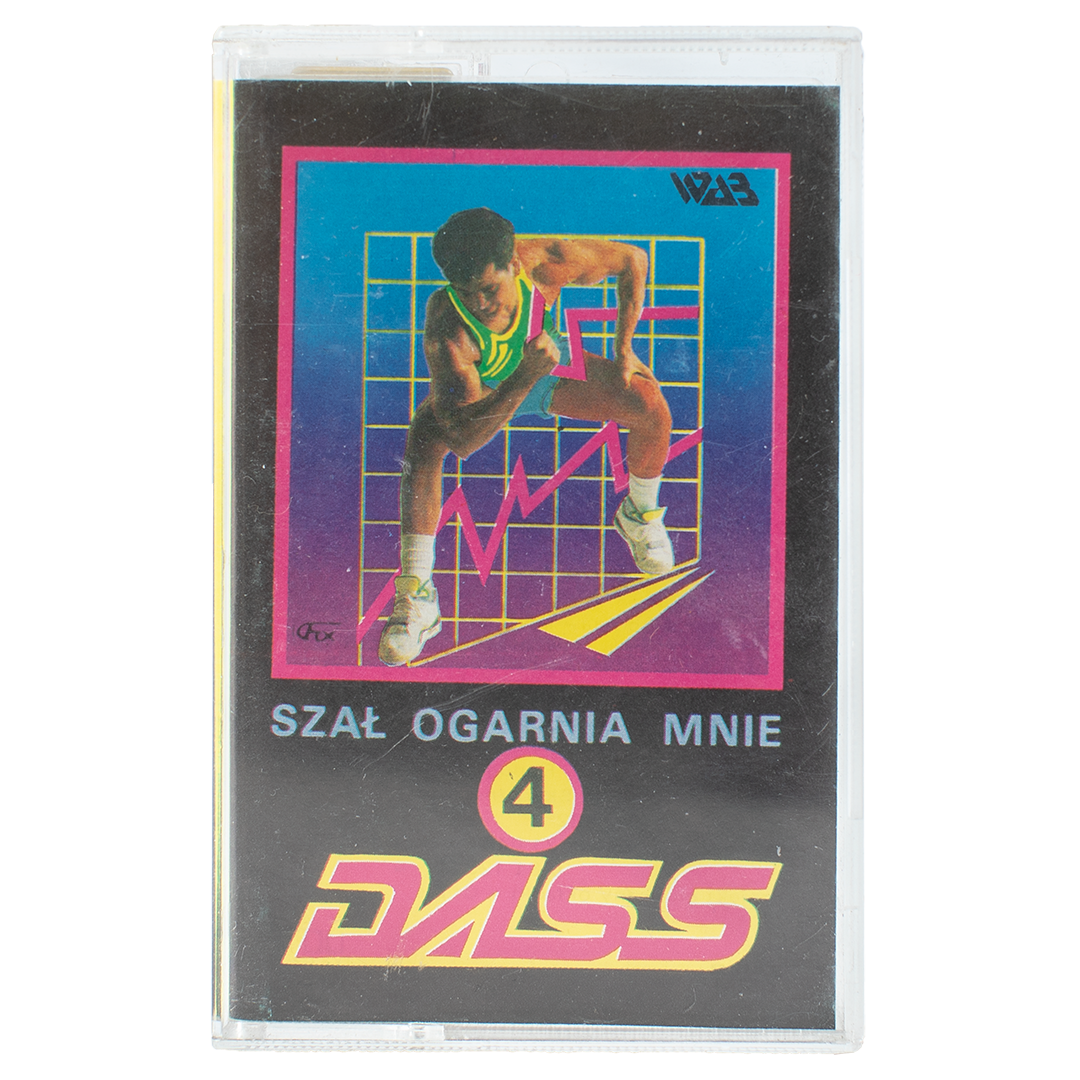

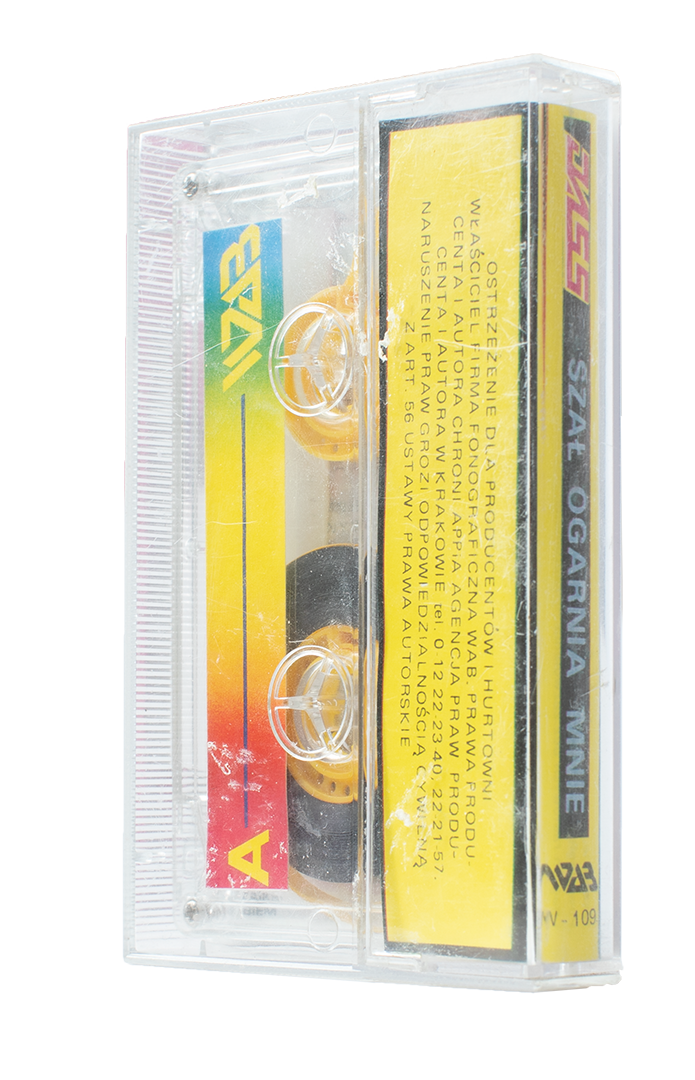

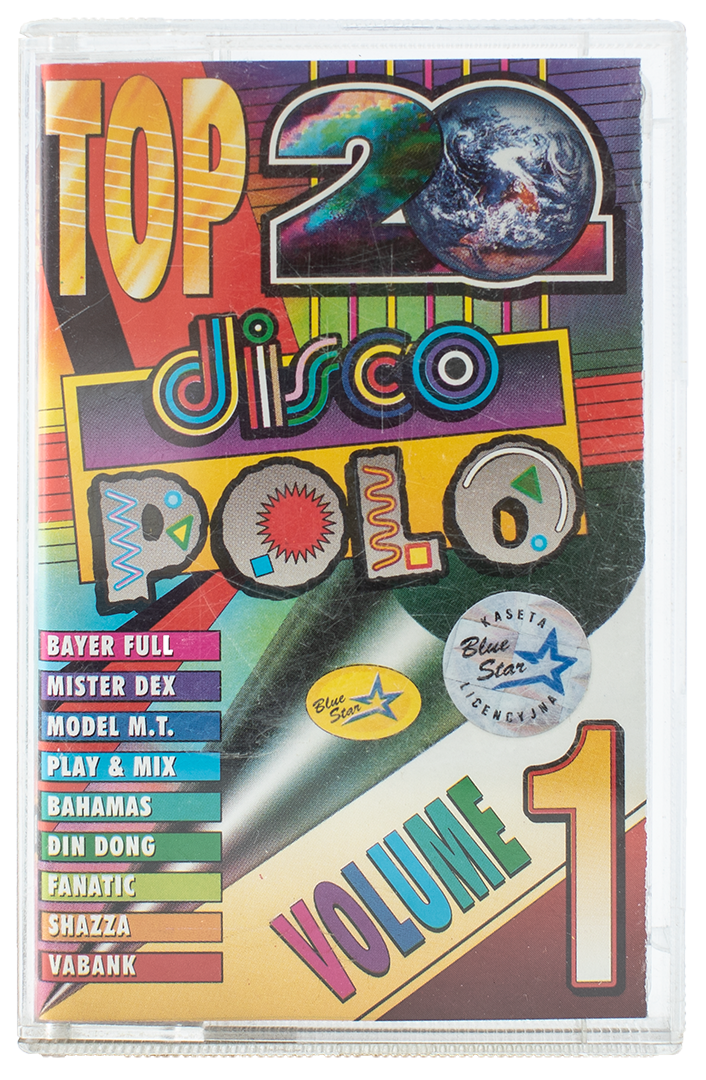

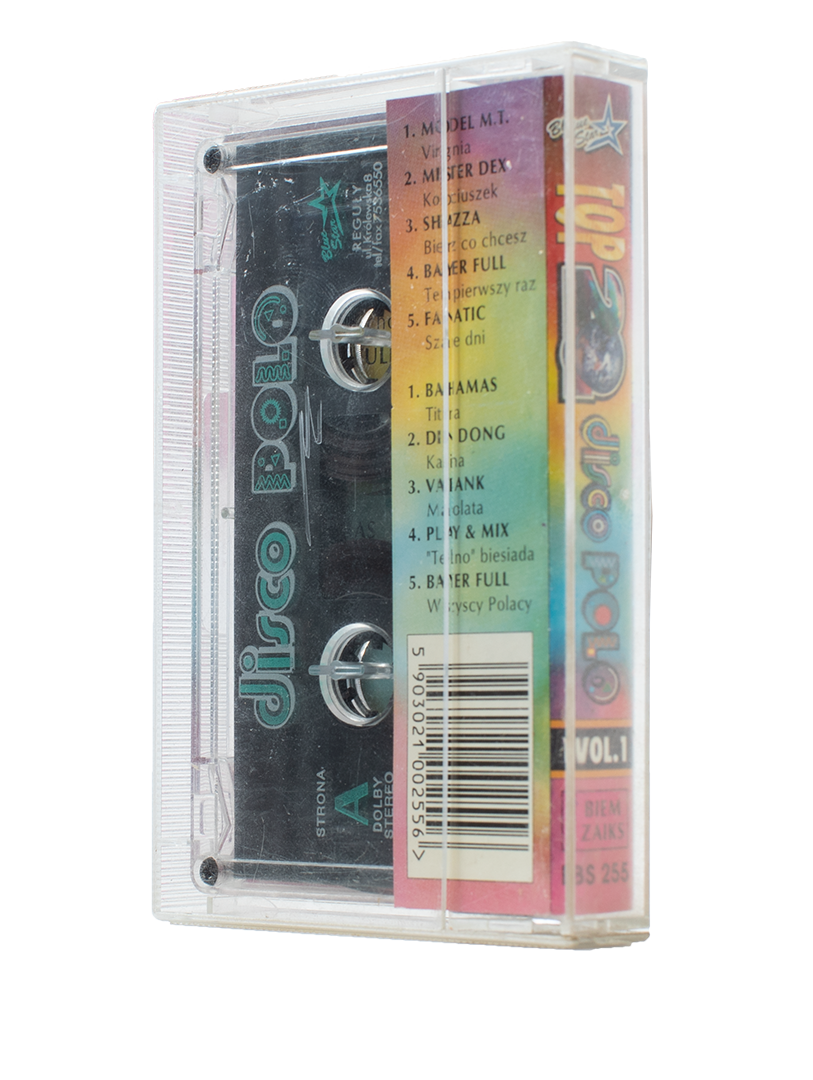

Artist/Maker Dass, Shazza, Top 20 Disco Polo

Date Production/Creation

Record label WAB/after 1991, Blue Star/1996, 1994

Entry in the museum collection

Outside collection, educational collection

Place of origin

Janów Podlaski, Lubelskie Province, Poland, Europe

Current location

National Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

Material

Plastic, cassette tape

Dimension

Length: 10.2cm; height: 64cm; width: 0.12cm.

Inventory Number None

Keyword Cultural heritage Music Memory

Copyright PME/NEM

Status Non-inventory

Image Credit Photograph by Edward Koprowski

Critics are often quick to dismiss pop culture as garbage. What can we salvage by picking through their rejects?

What is this object about, who are the people behind it?

The mass Disco Polo phenomenon grew out of the subsoil of Poland's post-1989 political and economic transformation. It was a reaction by a section of society to the incomprehensible debate about the possibilities of a capitalist economy, while also being one of the first expressions of capitalist audacity. Disco Polo production companies were among the first private initiatives on the music market, and the lack of control present at the time created opportunities for many abuses in the form of, for example, musical piracy. As a musical trend, aesthetically and lyrically, it presented Poles' ideas of the world we longed for: motorways, the West, exotic countries, eroticism. In the opinion of critics of the time, it was a musically and lyrically worthless product for the masses. As a cultural practice – present at feasts, weddings and fire station parties – it was seen as an expression of the bad taste of the lower classes of Polish society. Finding it of little value, they pushed it to the margins of culture, despite its widespread presence, thus building a social divide.

What places is this object related to, how European/transnational is it?

Disco Polo, like any product of contemporary culture, operates at the intersection of two spheres – the economic and the cultural – and as such can end up being relegated to the dustbin. It is not linked to specific places, but to social situations. It creates groups of participants who, for a brief moment, become a community constituted around having fun. As a result of the confrontation of different cultural models, Disco Polo – with its rather conservative orientation – loses in the symbolic battle against progressive tendencies. But it is nevertheless present in the mainstream. Stylistically, it is reminiscent of Balkan Turbofolk or 1980s Italo Disco. However, like those, it does not fit into the repertoire of high culture.

Why and how did this object arrive in the museum’s collection?

The Disco Polo music casettes came to the Museum as part of the "Cult Objects" project and the "Disco Relax" exhibition dedicated to the Disco polo phenomenon. Ethnography, despite its important historical dimension, which is even more accentuated in a museum context, is a field interested in the present and in everyday life. Disco Polo has been a subject of interest in academic circles, which has not been helpful in promoting its understanding by the wider public. The role of the Ethnographic Museums is to tell a story about a world that is both familiar and disregarded.

What is the relation of this object to waste?

The fundamental dimension linking Disco polo to the broader notion of waste in this case is the marginalisation and symbolic violence mainstream culture applies to competing models. In a hierarchical system, value-free culture and its manifestations are waste, no matter how many people ascribe importance to it. It is eliminated from the mainstream, and if it is present, it is in the form of a pastiche and a caricature that ridicules its participants.