Kaput prosvjednika od balona iz Ujedinjene Kraljevine pronađenih na belgijskoj obali, Bruxelles, Belgija, 2019.; © Kuća europske povijesti

Autor Laia Puig i Espar

Mjesto Edinburgh, Škotska

Datum 12/02/2023

In 2019, the House of European History (HEH) decided to create an exhibition on rubbish. But how to urge audiences to react to the waste crisis? How to make a bigger impact in society as a museum? And, is it fair to ask audiences to modify behaviours if the museum does not change as well?

These are some of the questions that emerged during the first meeting with the representatives of HEH’s partner institutions in Brussels (October 2021). To address them, ‘museum activism’ became one of the workstreams of the Partnership programme of Throwaway.

This concept can be used to define the work of museum professionals as advocates of change within their institutions and networks to influence positive change in society. Definitions of ‘museum activism’ tend to be broad, as they try to group very different kinds of practices and there is no standard way of classifying them. The concept, which has become increasingly popular in the sector, has found the opposition of those who defend that museums are – and should remain – neutral spaces.

I wanted to study how the partner museums of Throwaway interpreted ‘museum activism’, as this would give a transnational account on the phenomenon. I had conversations with the House of European History (Belgium), the Museo Guatelli (Italy), the Museum of Recent History Celje (Slovenia), the Museum of European Cultures (Germany), the Museum of Folk Life and Art (Austria) and the National Ethnographic Museum (Poland).

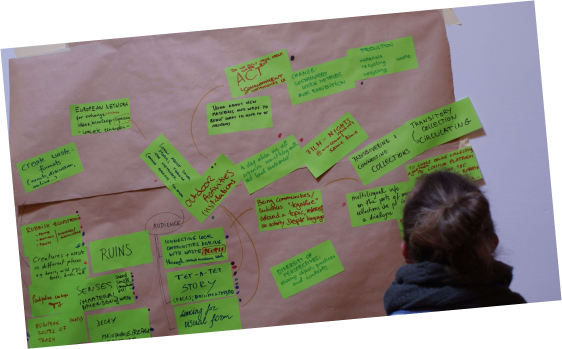

They shared with me a myriad of museum activism examples that I grouped into three different categories:

- ‘Externally facing’ activism, which is observed within the public programming of museums, that is, in the interaction of the museum with audiences.

- ‘Internally facing’ activism, which targets the museum itself and its employees.

- ‘Institutionally facing’ activism, which takes the shape of advocacy, or campaigns aimed at making change at government or policy levels.

You can read about these museums’ perspectives and examples in my article in the project publication. Like Throwaway, most of the cases I present revolve around sustainability.

Examples I explore in my article include producing exhibitions on topics like recycling or fast fashion; creating a green team run by ecologically minded staff members; adapting old buildings to make them more energetically efficient; reducing single-use plastics in the café and shops of the museum; re-using elements of old exhibitions in new displays; or creating advocacy groups to influence major policy changes around climate change.

I believe that the Throwaway project has been a turning point for the HEH because it has forced the museum to embrace new forms of activism, and to identify them as such. For instance, it is a circular exhibition and the project includes a local participatory process to reflect otherwise ignored voices within the exhibition narrative. The project has also sparked conversations about how waste can be reduced in the institution’s operations.

In my article, I address the limitations of ‘museum activism’, such as the fear of public backlash when openly campaigning for certain causes from the museum. Some practitioners I talked to are cautious and they do not use the word ‘activism’ to designate their activities. But, as I found, their institutions openly engage in the pursuit of social change, and most of their staff members agree that museums are powerful tools to influence society, proving that they do not consider the space as neutral at all.

In my view, activism (externally-, internally- or institutionally-facing) is not determined by what you call it, but by what you do as a museum practitioner.

It is our hope that Throwaway will inspire museums to articulate messages addressing the climate crisis and influencing change, regardless of whether they use the label of ‘museum activism’ when doing so.

Laia Puig i Espar

Cultural Consultant

Laia Puig i Espar is Exhibitions and Displays Officer at the National Museum of Scotland. She has worked as producer and curator on a diverse portfolio of cultural projects. These include disseminating history (the Centenary Exhibition at PEN International), widening access to literature (Engage!) and exhibiting future urbanism (Exit Design). She is interested in how narratives are constructed through exhibitions and can enact positive change in society. Hence, during her MA in Arts and Cultural Management at King’s College London she studied activist museums. She joined the House of European History as a Schuman Trainee in 2021, where she contributed to the activist aspect of the Throwaway project.

160

160